Book review of 'The Broken Heart of America' by Walter Johnson

A potentially good history book tainted by Theory

I am not an American, but perhaps like most people growing up with English as a native language, I have been steeped in American culture for as long as I can remember. I remain interested in the American project because it continues to impinge itself on a daily basis. I suspect the constant coverage of the United States in British media, which started long before Americans had access to these channels online, is at least in part because our journalists, novelists and pundits dream of making it ‘big’ there.

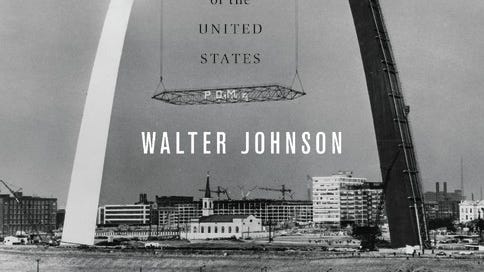

Walter Johnson, a Harvard professor, wrote The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States in time for it to be published during the fateful springtime of 2020, a month before George Floyd died. The author traces the history of St. Louis, Missouri, arguing for its special significance in American colonialism and racism. From the policy of ‘Indian removal’ during the settler period of the 18th and early 19th century, through the Civil War to the First World War and Depression, Johnson posits that this mid-Western city played a central role in making the United States what it is today. Particularly, in relation to white supremacy and racial animosity.

This narrow geographical approach offers a view into the USA and its history that I don’t often experience, based as it is on a single city (or two cities, counting East St Louis as a settlement in its own right). This book spans the full time that that the United States has been in existence, with a focus on what used to be called ‘race relations’.

The familiar tics of the white ‘progressive’ author writing about racism are visible in the text, such as capitalising Black but not white. However, it is in discussions of ‘whiteness’, the term supposedly derived from the work of black author W.E.B. Du Bois (a word which it is not clear to me that Du Bois used himself) that Johnson really gets unstuck. For example, the idea that German immigrants to St. Louis achieved ‘whiteness’ by supporting certain racist policies of the city administration suggests the author believes in the phenomenon as a property independent of skin colour, given that practically all German migrants to that city in the 19th century would have been white.

The implication of this distinction between white and whiteness is that black people have whiteness if they think other than how Theory predicts and demands they should, and more importantly, that white progressives can disown and diminish their whiteness, absolving themselves of racial guilt, if they try really hard to maintain correct, anti-whiteness thoughts and deeds.

I suspect that animosity which existed between rival groups of white migrants to St. Louis and the USA more generally, whether they were German, Irish, Polish or Italian in origin, really had nothing to do with ‘becoming’ white or achieving whiteness. Without having been there in the 18th or 19th century to verify my belief, I am confident that the native Americans and former slaves who lived in St. Louis during the settler period did not perceive the European immigrants as anything other than white. Perhaps this was because they did not have Theory to explain to them that whiteness is an acquired syndrome, having to do with the ownership of private property or some other economic factor. The binary thinking which assumes native and black Americans either didn’t own or didn’t make the effort to defend property is the progressive, patronising racism of assumptions and low expectations.

Neither do black or native people in St. Louis have agency, according to the neo-Marxist mindset evidenced in Johnson’s book. The author attacks Abraham Lincoln for taking the position that a victim of lynching should have received a fair trial, rather than Lincoln questioning why the victim should have been on trial at all. In fact, the man lynched had cut the throat of another man and stabbed someone else, which is why he was subjected to vicarious retribution. Theory requires all black people to be helpless victims of the white supremacist system, denying them the opportunity to act with intent, whether good or bad.

The portraits within this book of European revolutionary exiles playing a part in the American Civil War were interesting, but the implication that St. Louis was a hotbed of revolutionary activity falls flat. If the city really did have a strong tradition of working class solidarity and black community campaigns, why is the city as awful for black people as the author claims? If these revolutionaries genuinely cared about the lives of black people in the city, it would seem that either there were very few of them, that they enjoyed little popular support, or that their methods were ineffective. Possibly all three could be true. The implication is that white supremacy is all-pervasive and extraordinarily persistent across the centuries.

The message to any black people reading this book seems to be: join the (white-led) revolution, or forever be down-trodden. Like the (white) Frankfurt School Marxists who assumed that black people in the United States and elsewhere could form a ready-made revolutionary vanguard, the author’s intent appears to have been to construct a continuous narrative of injustice across the centuries, so that someone living in the USA today would conclude that the black struggle for civil rights has utterly failed. Why else draw a parallel between events that took place in St. Louis hundreds of years ago with more recent tragedies in the city, including the shooting of Michael Brown in 2014? The effect is to depress the reader into thinking that nothing has changed in the USA since the year 1619 or 1776, despite the context changing out of all recognition.

The idea presented in Chapter 9 of the book, that town planning in the early to mid 20th century was the implementation of institutional racism, is not supported by the facts. Very similar principles were applied to European cities at the time, many of which were virtually all-white in those days. The removal of poor people from down-town neighbourhoods in order to promote regeneration and private property interests isn’t necessarily racism in action. Here, Johnson is out of his depth, his lack of knowledge of town planning history all too apparent. That gentrification harmed black residents of St. Louis disproportionately is not evidence of racist design, because the same process has displaced poor whites in other cities where that demographic made up the majority of the urban underclass.

Similarly, the maintenance and safety problems which afflict high-rise housing projects of the post-World War II era affect all tenants regardless of race. These problems are just as bad in white Glasgow, Scotland as they were in the complex of eleven-storey towers in Pruitt-Igoe, St. Louis, now demolished. They are failures of modernism and the supposed economies of scale that were meant to derive from vertical living, not evidence of ‘racial capitalism’.

Johnson points out that women who lived in federal housing projects were penalised financially for having a man live with them in subsidised apartments. That is more usually considered to be an unintended consequence of welfare policy having a negative effect on family life. For the author, expecting black fathers to live with their own families is a discredited ‘racist, sexist and heteronormative’ notion. So, which is it? What is wrong with forbidding these men from living in the projects intended for single mothers if their presence is considered unnecessary by Theory?

In Chapter 10, Johnson refers to the federal housing projects in St. Louis as a ‘criminogenic environment’, as if the young black men he is writing about have no agency in their decision to commit crime. Once again, the tendency of the white progressive is to strip black people of the ability to choose for themselves, making them passive victims of a system entirely created by and operated for the benefit of white people only. Sorry, people with the characteristic of whiteness only.

In these circumstances, it is hard to imagine black success being possible, strongly suggesting that black people have been and still are being recruited as foot soldiers of the battle for social change that white progressives wish to bring about. Angela Davis, who gets a brief mention in this book as a visitor to St. Louis, was of course a student and special project of Herbert Marcuse.

As I completed reading The Broken Heart of America, I turned to the inside back cover to read the author’s biography on the paper flap. Walter Johnson, a white man, is Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. You’d think there would be at least one black person in the whole of the United States who knew black history, but apparently Harvard couldn’t find one. If that isn’t telling about America and the racism of progressive elites, I don’t know what is.

ISBN: 9780465064267

Published by: Basic Books

$35.00 hardback, $19.99 ebook or paperback, audiobook

https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/walter-johnson/the-broken-heart-of-america/9780465064267/

this is ridiculous, if you expect Black people to bear all of the responsibility of explaining racism to white people, you are part of the problem. Having people of multiple races interested in learning about African and African American studies is a good thing. He is absolutely not the only professor in that department at Harvard, and you are being ignorant to allude to that